Today we consider it a matter of course to concede civil rights to one another, among which are freedom of speech, free choice of domicile, free choice of profession, freedom of travel and of religion. If anyone is forced to belong to a certain religion or to practice a certain profession or to limit their mobility, we consider that unfair, even unworthy.

These rights to freedom are not something we may take for granted; far from it. They were only achieved during the Age of Enlightenment. What constituted the freedom of a Roman slave was the freedom of the slave owner to rent, sell or free them. But for a slave a life in freedom was unthinkable as long as they lacked property, the foundation necessary for their existence. No one without land had any claim to agricultural yield. Thus the slave owner guaranteed the slave’s existence, which the latter earned by cultivating the owner’s land. To release a slave without providing them with the possibility to make use of this freedom was not to release them, but to make them an outlaw. The only chance the slave had to make use of their freedom was either to find a new master or to go on serving the old one. Emancipation of a slave was oftentimes not an act of grace, but rather a delayed death penalty.

Today we are connected with this picture in various ways. First: Slaves had basic needs that had to be met for them to be able to work at all. No dead slave was a good slave. And we have remained beings of need to this day. We are neither free nor unfree against these needs; it’s just that our existence is endangered if they are not met. Only when my existence is guaranteed do I have questions that go beyond guaranteeing it.

Second: The work contract of a modern-day managed employee goes back to the law of tenancy to which slaves were subjected in Ancient Rome. The master––whom today we call the employer––owes the employee a living. In an economy based on external supply, this living no longer consists in making land available for subsistence farming, but rather in providing money to enable the employee the purchase of goods and services. As long as this income is guaranteed along with the safety regulations the labor unions have stood up for so commendably over the past century and a half, the employer is entitled to use the employee to serve their––the employer’s––goals and purposes. To be sure, since ancient times the employee has attained the status of a natural person and hence is subject to civil rights and obligations; nevertheless, the employer still disposes over their manpower and hence disposing over them as a beast of burden, the same as the Roman master over his slave, whom he was entitled to rent out, to sell or to destroy.

Third: The master took care of his underlings as head of the household and saw to it that they wanted what they were supposed to want. Living and working conditions were set up such that they had no choice but to do what they were supposed to. Since today in a society built around division of labor it is necessary to earn money in order to consume, the things we produce must necessarily make money. The only way to make oneself useful is by showing not obedience toward a master, but allegiance to the market. The master’s hand was visible, but the hand of the market has become invisible. But both hands have a raised forefinger and proclaim the following threat: If you don’t want what counts for us, we will withhold from you the things you need!

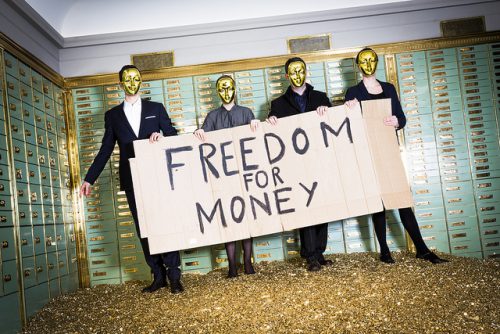

Now the question arises as to how we can set up our political and social circumstances in a way that civil liberties––from the freedom to choose one’s own profession to that of speech––do not seem as cynical as the freedom granted to a liberated but penniless Roman slave. The answer couldn’t be simpler: All we need to do is liberate the guarantee of a person’s livelihood from the conditions that hamper this guarantee. Let’s just grant everyone absolutely what they absolutely need. Why ought everyone be entitled to what they absolutely need? Because they need it absolutely! Any and all conditions attached to this need are inefficient. A guarantee on everyone’s existence is the most efficient way to maintain society––because everyone receives it.

Now the question arises as to how we can set up our political and social circumstances in a way that civil liberties––from the freedom to choose one’s own profession to that of speech––do not seem as cynical as the freedom granted to a liberated but penniless Roman slave. The answer couldn’t be simpler: All we need to do is liberate the guarantee of a person’s livelihood from the conditions that hamper this guarantee. Let’s just grant everyone absolutely what they absolutely need. Why ought everyone be entitled to what they absolutely need? Because they need it absolutely! Any and all conditions attached to this need are inefficient. A guarantee on everyone’s existence is the most efficient way to maintain society––because everyone receives it.

And what about the so-called dirty work? The notion of dirty work stems from an era when for the social elite all work was dirty, whereas for everyone else it was considered an unavoidable fact of life. On the farm the cows need to be milked, the crops harvested, the bread baked. The dignity of my doing this work derives from my acknowledgement that it needs doing––and simplifying, if possible. Today’s dirty work is a specter wreaking havoc in many fellow human beings. It’s hard to say just what work is dirty. Is it dirty to launder money? To wash the car? Or elderly people? Or dishes? And what work is clean?

There is no such thing as dirty work. There is nothing but work that somebody has to do and work that nobody has to. Today we indulge excessively in fake work that doesn’t need doing, simply because so many jobs are no more than places to earn an income. And today our vision for work that needs doing is blurred, our view clouded by our fearing for our existence.

Unconditional basic income enables us a clear view on what we owe each other. It allows me to recognize what I can do for others, and it makes sure that the laws guaranteeing civil liberty do not deteriorate into sanctimonious clichés like the one about the emancipated Roman slave.

Who’s supposed to pay for basic income? This is the best of all the false questions. Basic income doesn’t need to be paid for; it needs to be understood. In monetary terms it is a zero-sum game. It is not an additional income; it is a fundamental one. It does not lead to more money in the bank, but to the same funds being composed in a different way. As a rule, the other income earned previously drop in the amount of basic income a person draws. The account balance stays the same.

Unconditional basic income requires only a slight modification of the existing state of affairs: Guaranteeing unconditionally the portion of income that each individual needs in order to live. What, if you please, could possibly be so dangerous about that?

Excerpt from: Daniel Häni & Philip Kovce (2016): Voting for Freedom: The 2016 Swiss Referendum on Basic Income – A Milestone in the Advancement of Democracy, 180 p., EUR/$ 12,99.

Daniel Häni is Entrepreneur. He is Co-Founder and CEO of Switzerland’s biggest Coffee-House “unternehmen mitte,” as well as Co-Initiator of the Swiss popular initiative for an unconditional basic income. The initiative was successfully submitted in 2013, and received media responses worldwide.

Philip Kovce is Associated Research Fellow at the Chair of Economics and Philosophy at Witten/Herdecke University, Germany’s first private university. He is a member of “tt30,” the Club of Rome’s young leaders Think Tank, and works for several German newspapers as well as broadcasters.

Image source:

Thumbnail: “Grundeinkommen_Weltrekord” by Hanes Sturzenegger via flickr, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0 // “Weltrkord fürs Grundeinkommen” by Michael von der Lohe via flickr, CC BY 2.0